From the outside, things looked okay. I had a nice apartment, good friends, a longstanding job as a lawyer with New York City’s Department of Finance. But inside I felt empty. Day after day, I tracked down corporate scofflaws, calling them up and confronting them about the thousands of dollars they owed the city. It was necessary work—somebody had to do it—but over the years, steeling myself, I found I had become so callous. Life was drained of its colors.

I used to drop in at a tavern in Greenwich Village after work and unload on a bartender there, Angelo. The place had these big paintings on the walls, brilliant acrylic portraits. One showed folks sitting around a card table playing bridge with all the details beautifully painted, even the cards. It was not what you’d expect to see in a bar—nothing generic about it—and one day I asked someone who the artist was. “Angelo,” he said.

I was flummoxed. Angelo, the bartender? In his free time, he created beauty with paints and a brush. He nurtured his artistic side. A side I had myself but had somehow let languish. How long had it been since I’d even tried to draw? What would Miss Wiener think?

Growing up, I was studious, quiet and curious. I wanted to see—really see—everything in the world outside our Brooklyn apartment. I was one of three kids, and I’d sit for hours at our kitchen table, copying pictures out of TV Guide or Life magazines. I remember studying Jackie Kennedy’s bouffant hair in a picture—the same way our teachers at school were starting to wear their hair. I wondered how it worked, so I copied it carefully, penciling each strand of hair in her bangs. Drawing was an incredible way of understanding things.

I once drew a picture of LBJ when he was elected vice president. His big floppy ears and the bags under his eyes fascinated me. I must have captured something about him because, when I brought in the picture and showed it to my teachers, they put it up in the hallway. That was where Miss Wiener saw it.

Miss Wiener was brand-new that year at P.S. 113. Only 21 years old, she was given all the jobs the other teachers disliked, like taking care of the hamsters, the goldfish and the turtles. During recess, instead of going outside to play stickball—which I wasn’t very good at—I used to stop in and study the animals. I’d sketch the geometric patterns on the turtles’ backs.

“You drew that picture of the vice president,” Miss Wiener said one day.

I nodded.

“You’re a good artist, Ronald,” she said. “Do you have any more pictures to show me?”

It was like a light went on. An adult was really interested in what interested me. Mom was loving and nurturing, but she had her hands full just getting us to church. It was altogether different to have a teacher express her enthusiasm, one who seemed to know a lot about art. Miss Wiener brought in books she got at the library of famous painters like Gauguin, Renoir and Rembrandt. I especially liked Rembrandt. His portraits looked so real, I could imagine the people stepping right out of them and talking to me.

I had never actually painted, but I loved studying the colors and seeing how an artist could show things with just a few deft touches, the light on a hand, the shadow or shade on a face.

“Let me take you to a museum,” Miss Wiener said one day. She had a tiny car, a Renault Dauphine, about the size of a VW Bug, and she drove me into Manhattan on a Saturday. We trooped around the city, visiting the Museum of Modern Art, walking up the ramps that sloped around the walls of the Guggenheim, seeing some real Rembrandts at the Metropolitan.

Miss Wiener looked as if she could have been painted by one of the artists we saw, Modigliani. She was slender with pale skin and red hair, and I could imagine how he’d depict her features, her direct gaze and that quick smile. She opened the door to a whole new world for me. She even signed me up for art classes at the Modern and drove me to them.

Other kids were good at sports. I drew. It’s what I did, and Miss Wiener showed me the many different ways an artist could express himself. Thanks to her encouragement and support, I got into a good middle school. In seventh grade, I ran for student body president. I drew multiple self-portraits for my campaign and my face was plastered all over school. I won.

Neither of my parents had gone to college. My mom would have loved becoming a teacher like her sisters back in Virginia, but she worked too hard to support the family. And Dad…well, Dad had his demons.

It’s not hard to see why I felt called to be the super-responsible one, the middle child, the one getting awards at graduation. College was an obvious choice for me. I loved the academic challenges and was a motivated student. Law school seemed a logical next step for a history major like me. I wanted to be able to get a good job and make everybody proud.

The artistic side of me got lost. I might blame the art teacher in college. He did everything he could to make his classes unappealing, scheduling them at an ungodly early hour and then criticizing his students’ work with undisguised disdain. He was no Miss Wiener. Later came the demands of school and the law and chasing down scofflaws… until I seemed a stranger to myself and found myself wondering why my life felt drained of color. I had to make a move before it was too late!

The first thing I did was take myself back to church. I found a congregation I liked, with people who could talk about God and prayer in one sentence and then tell you about a great new restaurant in the next. Faith and community become one in my life.

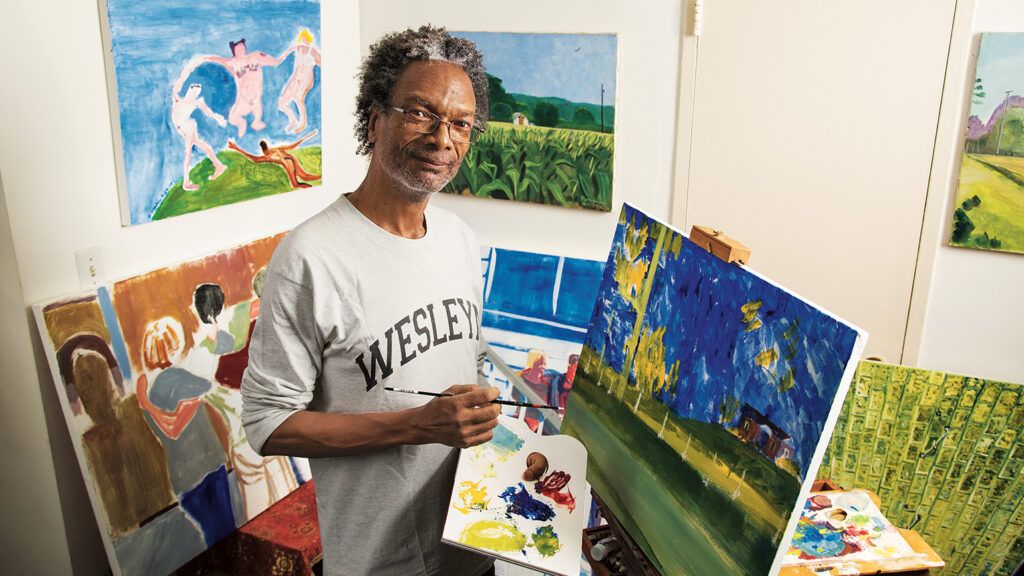

And then there came that moment in the bar. What if i tried to paint like Angelo? What if I asked him for help? I bought some supplies and christened a corner of my apartment “my studio.” I immersed myself in painting. I’d tackle a big canvas, hearing Miss Wiener’s voice in the back of my head, then I’d ask Angelo if he could give me some advice. We even worked together on weekends. Angelo taught me how to mix colors, how a complementary color could be used to make something darker. If you put green next to red, you’d get a vivid shadow and shading. He’d get out his brush and rework what I’d done, showing me how to do it.

I took out some family albums and worked from old photos, making portraits of relatives, most of whom were long since gone: Aunt Delilah, Aunt Nannie, Aunt Luella. Their features would come alive with a few flicks of my paintbrush. One day I found an old picture of my father, who had died from alcoholism when he was only 54 years old. In the photograph, he was still a young man—thoughtful, studious yet already prematurely old. What was he thinking? What made him tick? Why had he made the choices he had?

Copying the picture in a painting was like meeting him for the first time. Like I said, art had always been a way of understanding things. Not that I would ever fully understand my father, but I saw him differently after that. Painting was a way of forgiving, like saying the Lord’s Prayer with a brush.

I

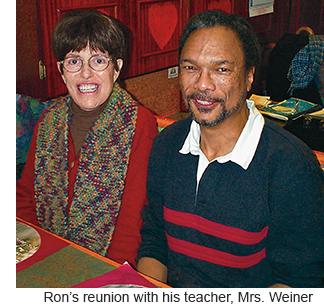

She was Mrs. Wiener now—she’d married a man with the same last name—and had moved to the suburbs, where she was the headmistress of a small school. Her son told me that she’d been suffering from cancer and wanted to see me again.

She came into the city, and we met at a restaurant on the Upper West Side, not far from my new church. She still looked like a Modigliani portrait, only she now had gray in her hair. There was something else I had never noticed as a kid—she had a very strong Brooklyn accent. But we were both very different people now. “I’ve taken up painting,” I told her. “I do portraits of people I love.”

I wished I had been able to take Mrs. Wiener to my studio in Brooklyn, where I could show off my work, but she didn’t live long enough to be able to make that trip. All too soon, I was visiting her grave. If only I’d been able to tell her how she had changed my life. Let it never be forgotten how one person’s interest in you, their willingness to encourage you, their ability to draw out your gifts can make a difference. A life difference.

It’s never too late to begin doing all the things you know they would love you to do. Never too late to discover what passion animates your spirit.

I am now retired from the law and paint full-time. I paint images that I see on Facebook or capture the faces of friends from church. Each blank canvas is a new challenge, an opportunity to see and to show. Each painting is a new expression of myself, filling me with joy. Each painting is another step in a new life.

For more inspiring stories, subscribe to Guideposts magazine.