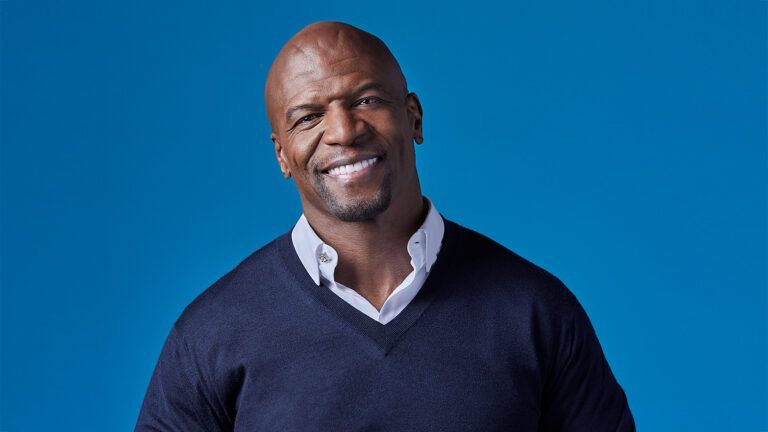

September 28, 2002. I came to work at the Allegheny County medical examiner’s office in Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania, where I was chief forensic pathologist. A new body had come in, that of Mike Webster, a former professional football player who had died penniless at age 50, presumably of heart disease. “He was a great Steeler,” said one of my colleagues. “A Hall of Famer.”

I knew little about pro football. I’d grown up in Nigeria and never been much of a sports fan. But I had seen something on the news about Webster, how this star athlete had descended into drug addiction, homelessness, dementia and depression.

In the morgue, I peered down at his body. As always when preparing to do an autopsy, I asked for God’s guidance. Then I whispered, “Something happened to you, Mike. Help me understand.”

My job was to establish the cause of death, which is both a legal and medical determination. Yet the underlying factors can be more elusive. In Mike Webster’s case, I suspected depression was at the root of his suffering, a suffering I knew all too well.

I was the sixth of seven children. All of us were expected to achieve great things. “You are here to make a difference in the world,” my father often said. He’d grown up in Nigeria begging for food on the streets. Through hard work, providence and dedication, he’d become a successful engineer and a leader in our community.

Dr. Bennet Omalu’s Inspiring Life and Career |

My siblings were all high achievers. I didn’t really fit the mold. I was anxious, unsure of myself. I did well enough in school but struggled to make friends. Dad had decreed that I become a doctor, at age 15 I passed a rigorous exam and was able to enter medical school. All I really wanted to be was a pilot, soaring aloft and seeing the world. I dreamed of going to America someday.

The demands of med school were unrelenting. I was younger than most students. I did okay in biology and biochemistry, yet I felt so disconnected from the work. I wanted to sleep all the time. I fell further and further behind. By the second year, I could barely get out of bed in the morning.

One Sunday, I was heading to the library to cram for a test and looked at all the other students talking and laughing. I sat down on a bench, disconsolate. What was wrong with me? Why couldn’t I laugh like the others? I retreated to my room, fell into the bed and didn’t move for the rest of the day.

Desperate for answers, I visited my sister Uche, who was doing her medical residency in the same city. “We’ll get you some help,” she said. A doctor said I was suffering from an “adolescent crisis” and prescribed group therapy. I didn’t go to more than a few sessions. I took a bus to another sister’s house 350 miles away. “It’s a school holiday,” I lied. I just wanted to hide.

From her backyard, I could watch the planes flying to and from the airport. If only they would take me with them. In America, people didn’t suffer like I did. They had the freedom to do whatever they wanted. That’s what it looked like in movies.

“You will find freedom once you finish school,” my sister Uche said when she came to get me. She talked to my professors, and I was able to make up the classes I’d missed. I finally graduated. But there was none of that freedom Uche had promised, only this gloom inside. It followed me to my first job, where as part of a Nigerian service program, I had to work as an emergency room physician and a doctor in a clinic for one year. I was able to help many of the villagers, but their needs were so overwhelming, I felt inadequate. Why had God made me a doctor?

I thought the answer came one day when I found a letter on my desk from the World Health Organization, which was looking for visiting scholars. Who put the letter there I’ll never know, but I sent in my application to both the WHO and the University of Washington, one of the participating universities. In September 1993, I got a letter, postmarked Seattle. “Dear Dr. Omalu, we are happy to inform you…”

It seemed as though all my dreams would come true. God had opened a door for me. “Thank you,” I prayed. “I promise when I get to America I won’t pester you so much.”

How wrong I was. Everything about America was confusing. I’d spoken English all my life, but suddenly people didn’t seem to understand me. Professors ignored me when I asked questions. Many people I met assumed I was uneducated and treated me like a servant. In Africa my skin color didn’t make any difference. Not here.

And yet I couldn’t stop believing that I had a future in America. Going back to Nigeria would be humiliating. The fellowship was for one year. The only possibility of staying longer was to be accepted into a residency program to become a practicing physician in America. Otherwise my visa would expire. I sent out 150 applications. I applied to several hospital programs in pathology. I liked that pathology was about solving mysteries and didn’t require interacting with patients. I got only two interviews. I was not offered a position.

I cried out to God. “Why give me a dream, only to take it away?” I wanted to shake my fist in anger. I felt betrayed.

One morning, the phone rang. “I’m Dr. Navarro, a professor of pathology at Columbia University and director of the residency program at Harlem Hospital Center,” the man said. “One of the doctors we offered a residency to has declined. We’d like to offer the position to you.” My head spun. I accepted immediately. Maybe God had a plan for me after all.

My first rotation at the hospital in Harlem was in the autopsy room—an examination of a man who had died of AIDS. It was 1995. I’d worked with cadavers before but only to study anatomy. I was new to pathology. I was charged with using all of my skills, all of the knowledge I’d gained, to answer one question: How had the disease killed this man?

I suited up in protective gear. Inside the autopsy room, the chief resident was there to guide me. “Let’s get started.” He pointed to where I should make the first incision.

I’d never seen anyone so emaciated. This poor man… I wanted to throw off my gear and run. But I had to persevere. There was a reason I was here. I wrote on my worksheet: “Hair, black. Eyes, brown. The body is in poor condition, with multiple lesions….”

I stared at the man, but a different feeling came over me. I no longer saw a body. I saw an individual, a human being just like me. Someone’s brother, a boyfriend or husband. What had seconds ago repulsed me now called to me. This, I realized, was where God meant me to be, to provide dignity to people otherwise forgotten. His children.

I took sections of the man’s organs and tissues to analyze. Two hours flew by. The autopsy was finished. But that sense of purpose I’d felt was permanent, as if a plan had been revealed to me. The gloom that had enveloped me for so many years had finally lessened.

Dr. Navarro helped me analyze the slides I’d made. The autopsied man had died of acute respiratory failure, due to a type of pneumonia that strikes only immune-suppressed people, such as AIDS victims. At the time, the reasons weren’t fully known. I hoped my work might help. It felt as if I’d done something important, as if determining the cause of death gave meaning to death.

My depression didn’t lift immediately. But as the months and years passed, I discovered a life purpose in my career as a medical examiner. I was doing as my father had wished but following a path that was my own and God’s. I stayed in America after the residency and got that job in the Allegheny County medical examiner’s office.

Now I stood over the body of Mike Webster, who had inexplicably spiraled down from hero to homeless, depressed and addicted. How could that happen? I looked first at the brain. I felt an answer would be found there.

In slides of his brain tissue, I saw the visual record of what those blows to the head, accumulated through the course of his career, had done. A degenerative disease hid deep within his brain. I subsequently saw the same in other football players.

I was the perfect person for the task. Not being a football fan, not having been born in America, I could ask questions others had dismissed. And having suffered myself from depression, I understood the gloom these players felt, a common component of chronic traumatic encephalopathy, or CTE, a concussion syndrome that produces cognitive decline and other symptoms. The evidence was in the brain lesions I first saw in Mike Webster. I asked him what had happened, and his brain tissue told his story.

I testified about CTE before Congress and eventually was portrayed in a movie starring Will Smith about my bringing this issue to light. In my life, the light that led me from depression was the light of God, who has guided me in the darkest of times and the best.

For more inspiring stories, subscribe to Guideposts magazine.