The night before the doctors removed my father from the ventilator, the last night they said he’d be alive, I sat by Dad’s bedside in the hospital and said all the things I needed to say. I held his hand and told him how much I loved and admired him. I assured him that I would take care of Mom. I thanked him for all he had taught me.

“It’s okay,” I said. “You don’t have to worry. You can just let go.”

Dad could only gaze back at me. He couldn’t speak because of the tube in his throat from a tracheotomy. He had Parkinson’s, lung cancer and now an infection. He lifted his eyebrows. I love you. That was all.

I squeezed his arm and left the room. I slumped against a wall in the hallway. He’d been in the hospital for months. This was it. The end I’d been dreading. How could I go on without my father?

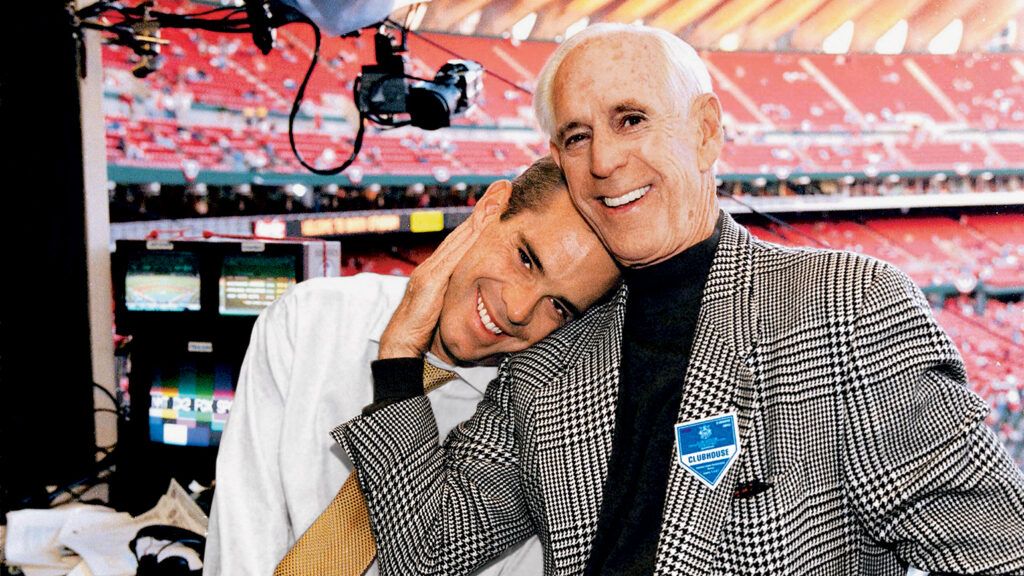

Millions of baseball fans knew my father, Jack Buck, as the gravelly radio voice of the St. Louis Cardinals. For 40 years, in that funny, folksy, self-deprecating style of his, he had served as the heartland’s storyteller, until he had become as beloved as the Cards’ most legendary players. At the entrance to Busch Stadium, around the corner from the statue of the great Stan Musial, there is a sculpture of my father holding a microphone. And in Cooperstown, New York, there is a plaque commemorating his election to the National Baseball Hall of Fame.

But to me he was Dad, my best friend, my hero. I followed him into broadcasting, eventually becoming his partner, calling Cardinals games. Nine years ago I began a second job telecasting the big national sports events, including the World Series. I was on the road a lot those days, but still I called my dad after every game. I wanted his input and advice. I wanted it still, on this unbearable night. After you go, Dad, the city will honor you, I thought. But what will I do?

I drove home in a daze. The next morning I called the hospital. My mother answered. “He’s still with us,” she said.

I had a Cardinals game to broadcast that evening. From Busch Stadium. First place was at stake. I’d told the radio station I’d be there. But now I was having second thoughts. How could I go, with my dad breathing his last a few miles away? That afternoon I drove to the ballpark to prepare. That meant mixing with the players, coaches and managers to gather personal stories to share with my audience—anecdotes of life on the road, a practical joke pulled in the clubhouse, how a player had emerged from a batting slump. It was a trick Dad taught me.

“How’s he doin’?” a coach hitting fungoes asked.

“Hang in there, Joe,” a player said.

My earliest childhood memory is of being in a broadcast booth with my father. I was three years old. He was on the air, in the middle of describing a play, when I spilled Coca-Cola all over him. My dad shot me a look I will never forget. I burst into tears.

But not even that could keep me away. I was the only one of Dad’s seven kids who tagged along with him to the radio booth. I was a big baseball fan, and I loved being around the game. Mostly, though, I loved spending time with my father. He was on the road a lot, so any chance to be with him was a treat.

Dad grew up poor. He hawked newspapers as a seven-year-old. Later my father took on odd jobs—short-order cook, crane operator, deckhand on an iron ore boat—anything to help the family. At night he worked on his voice by reading the sports pages to his father, who suffered from cataracts.

Thanks to my dad, I never had to struggle like that. But I shared his appreciation for hard work. Dad never pushed me to follow in his footsteps. He didn’t have to. Starting when I was 13, I’d drive with my father to Busch Stadium, and while he was broadcasting the game to millions I’d call the action into my tape recorder in an empty radio booth. We’d listen to the tape on the drive home.

“What do you think?” I’d ask.

“Work on your diction,” he would say. “The first rule for a play-by-play man is that he be understood. The second is: bring the action to life.”

My dad gave me plenty of advice—“Just be yourself,” or “Remember, you’re not the star; the game is”—but I never really knew if he thought I was any good. Then for my eighteenth birthday he took me on a road trip to New York for a Cardinals-Mets game. I was sitting in the back of the booth, soaking up the atmosphere, until I heard him say over the air, “Now to take us through the fifth inning is my son, the birthday boy, Joe Buck.”

I snapped out of my seat, totally unprepared. “Please, don’t make me do this,” I said to him off-mike. “I’ve barely been following the game.” My dad just smiled, and he and his broadcast partner left the booth.

I had no choice. I sat in his chair—Dad’s chair—and started talking. I tried to imagine that I was Dad. That I had his authority, his knowledge of the game. Thankfully, nothing major happened. And no fans called to complain. “I had to prove to you that you could do it, son,” Dad told me.

Three years later I landed the Cardinals job. My father and I were the broadcast team. The first game we called together was opening day, 1991—the Cards beat the Cubs, 4–1, at Chicago’s Wrigley Field. What I remember most about that day is that in the third inning it dawned on me that my father was my partner and I didn’t know what to call him. Between innings I turned and said to him, “I’m certainly not going to call you Dad on the air.”

Dad laughed. “Don’t call me anything. Just start talking. I’m the only other guy here. I’ll know you’re talking to me.”

We got so comfortable in our eight years on the radio that eventually I did start calling him Dad on the air. By then his Parkinson’s made his hands shake. I knew our time together was limited. I figured, Why not let the listeners know how much I love him?

Those years together meant everything to me. All that time my father spent away from home when I was little, I got it all back. It was as if God were making it up to the both of us. On the road, we stayed at the same hotel and had lunch together every day. How many guys in their 20s get the opportunity to spend that kind of time with their dads?

It was near the end that I came to admire my father more than ever. Dad got the most out of every minute he lived. His hope for me was that I’d do the same. One night, after he’d undergone radical surgery, he looked up at me from his hospital bed. “I know you’re thinking of buying a house, and that you’ve been putting it off because you’ve been so concerned about me,” he said. “Go ahead. Don’t put off what’s important. Live your life.”

Now the moment I had dreaded had finally arrived. The next breath Dad took could be his last, and here I was miles away in the broadcast booth, waiting for the start of another game. I looked over to where he used to sit. The chair was empty.

“What would you do?” I whispered.

The answer came in an instant. Dad had never missed a game in his life, not until he got really sick and landed in the hospital. He wouldn’t want me to miss this one. I sat down behind the microphone, and the Cardinals took the field.

I told baseball stories between pitches, just as he would have done. I called the plays, hearing his advice: “Remember, you’re not the star; the game is.” Between innings I talked to my mother. Dad was still breathing. Dear Lord, I prayed, I’ve got to let him know I’m going to be all right. The Cardinals scored six runs in the first three innings and vaulted into first place with a 7–2 victory.

After the final out, I rushed back to the hospital. “He’s still holding on,” Mom said. Dad was tucked in, now without any tubes or wires attached. I leaned in close and said, “I’ve got you covered. Everything’s going to be fine here.”

How could I be so sure? Because my father had taught me so well. As much as I was going to miss my dad, I would remember him—honor him—in everything I did. That’s how I would move on past the numbing grief.

Dad died five minutes later. But a part of him has never gone. I still feel him every time I do a broadcast. I’ll be calling the action, and I’ll look at the chair where he sat and know his spirit is never far away.

For more inspiring stories, subscribe to Guideposts magazine.