My wife, Patricia, knows. I always have my Orvis fishing vest and two backpacks at the ready. I took them with me to Haiti after the earthquake in 2010, to New York when Hurricane Sandy struck in 2012. Last year, I went to Houston in Harvey’s wake. Two weeks later, Hurricane Maria ripped through Puerto Rico. I needed to go.

I am a cook. I came to the United States from Spain and opened a restaurant, Jaleo, which just turned 25 years old. I now have more than 30 restaurants, from fast casual to Michelin-starred. My team and I feed the few, but I also believe in feeding the many. That’s why I volunteer at places like DC Central Kitchen, learning about the world outside professional kitchens. I have also learned about the spiritual world: I’ve twice walked the Camino de Santiago in Spain, a route walked by thousands of pilgrims each year.

While food will restore us physically, churches restore us spiritually. When I arrived in Puerto Rico, the island was in trouble like I’ve never seen before. Flying into San Juan five days after Maria, I could see the destruction: roofs ripped off, homes peeled open like tin cans, toppled trees stripped of every leaf. And when I landed, I saw that people were hungry. There was no electricity, no fuel. The entire island was shut down. I knew I needed to get involved.

I had already established a nonprofit, World Central Kitchen, where professional chefs could come together to feed the hungry. Before going to Puerto Rico, we went to REI and bought solar lamps, water purification pills and basic survival items. I took out as much cash as I could from the ATM—no telling when banks on the island would reopen. In San Juan, we rented a four-wheel drive. Driving was a test of nerves. No traffic lights. Downed phone and power lines everywhere. I thought we could set up at the Coliseum, or El Choli as it’s called, San Juan’s biggest sports arena. But as I’ve seen time and again, red tape was our biggest enemy. We were told that the kitchen could be used to feed only the people working there. One hundred and fifty of them. When millions were in peril of starving!

Where next? We needed a loaves-and-fishes miracle. When people tell me something can’t be done, I am even more determined. I knew a lot of chefs on the island. We headed to my friend José Enrique’s place in historic Santurce, a neighborhood usually crowded with tourists. Everything was dark, but José’s generator was working overtime. “Bienvenido,” he said, giving me a hug.

He’d been feeding the hungry with his sancocho stew. The lines were huge. “We run out early every day,” he said.

“We can help,” I told him. José’s place became our center of operations. We’d serve sancocho outside. Inside we set up a sandwich-making assembly line run mostly by volunteers. What we needed were supplies, literally tons of them.

I served two years in the Spanish Navy, sailing on the tall ship Juan Sebastián de Elcano. I’ll never forget coming into New York Harbor on July Fourth and seeing Lady Liberty and hundreds of boats flying the American flag, a symbol of all that’s good about this country. I became a U.S. citizen in 2013, alongside my wife. I knew that citizenship came with an obligation to make a positive difference, to improve the lives of my fellow Americans.

The biggest food supplier in San Juan was José Santiago. We drove to his place. We needed bread, cheese, vegetables, plates and utensils. We’d have to buy on credit. The cash in my backpack wouldn’t go far. As we talked, I was amazed to see a picture of the Juan Sebastián de Elcano on his wall. “That’s the boat I sailed on in the Navy,” I said. He asked where my family was from. “Asturias,” I said. His people had come from Asturias too. That did it. We shook hands on a deal and filled up the four-wheel drive.

The loaves-and-fishes miracle was becoming a reality.

Back at José Enrique’s place, we gathered our team, a growing group of chefs. I sketched out our needs on a flip chart. ENERGIA—gasoline, natural gas and diesel. ALIMENTOS—dry goods and fresh goods, especially water. COMUNICACIÓN—social media to get the word out. VOLUNTARIADO—volunteers. When I helped out in the Rockaways in New York after Hurricane Sandy, I saw what a group of very organized church volunteers could do. The Southern Baptists were everywhere, dishing out mashed potatoes, chicken tenders and gravy. Their mission: to be “the hands and feet of Jesus to people seeking hope during a time of crisis.”

We could do the same. We could learn from them. We branded ourselves #ChefsForPuertoRico and set up a WhatsApp group. Phone calls and e-mails were unpredictable, but WhatsApp worked. I insisted on preparing hot meals and sandwiches. In a moment of crisis, a simple sandwich looks like heaven. And if you feed the people, you are creating an army of first responders. They in turn help others.

We found food trucks, drivers. We fed the local police, and they donated diesel in return. We kept doubling our output. From 500 sandwiches to 1,000, from 2,000 hot meals to 4,000. Soon we were doing 10,000 meals a day. Could we do more? More than the government?

I often thought of something my father told me. We would cook paella over an open fire on weekends. I, of course, wanted to help. “Build the fire,” my father said. Gathering wood, building the fire—these didn’t seem as important as being the chef, stirring the paella. One day, I complained. My father replied, “The fire is everything. If you don’t control the fire, nothing else matters.”

The fire for us was building this network of helpers. Anybody and everybody. We reached out to corporate donors: Goya Foods sent supplies, UPS sent bottled water, Chili’s restaurants donated thousands of pounds of chicken. A restaurateur friend was abroad when Maria hit, but he sent me a message: “Take everything out of my refrigerator and anything in storage.”

I went back to the Coliseum. This time my efforts were successful. Soon El Choli was a buzzing scene inside and out, generators humming, the scraping of huge paella pans, cooks heaping mountains of rice in stock. So many amazing volunteers came to help.

Sometimes a priest would lead us in prayer. But those weren’t the only prayers. One cook said “God bless Puerto Rico” every time she poured oil into a pan of rice. The blessing was the exact amount of time for the oil she needed.

I felt like I was living two lives. I’d hear from our R&D department in Washington, the general manager at our new Zaytinya in Texas, the chef at our new restaurant in Beverly Hills. Then I’d talk to the cooks and volunteers about the sandwiches they were making. “More mayonnaise,” I said. “The sandwich has got to have fat, calories, to be moist. And it has to taste good.” A plate of food is more than food. It sends a message that someone cares about you, that you are not on your own.

We fed the National Guard and Homeland Security. Partnered with the Salvation Army and the Red Cross. We partnered with FEMA—eventually. But this network of restaurants and chefs made it happen. We even had a pastor in the hills, Eliomar Santana, who insisted on using his church’s kitchen to feed his community. We sent meals to the elderly, the homebound, hospitals.

Both of my parents were nurses, so I understand the stress that the hospital workers were under. Air conditioning, ventilators, operating rooms barely functioning with old, unreliable generators. This is what they were facing while working to save lives every day.

Still, we overcame blocked roads and collapsed bridges, red tape, supply bottlenecks, lack of electricity. To date, we have served over 3.5 million meals with 20,000 volunteers working across 25 kitchens. It has been hot, sweaty, exhausting work. But it has also been life-changing. My friend Robert Egger once said, “Too often charity is about the redemption of the giver, not the liberation of the receiver.” Our food was liberating.

I went back at Thanksgiving with Patricia and our three daughters, and we cooked to thank all those who had helped after the storm, especially the chefs. Chefs understand how to create order out of chaos, just as they know how to control the fire. There were times when we didn’t know what to do. But we kept cooking. And the fire kept burning.

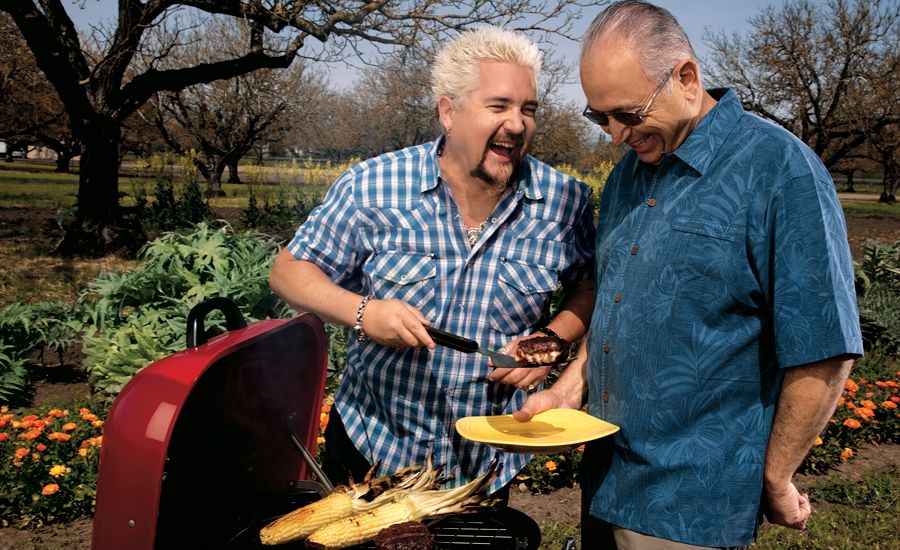

Sadly, there is always another natural disaster around the corner. While most of our team was in Puerto Rico, we watched from afar as wildfires devastated Sonoma and Napa counties in California. My friend Guy Fieri began cooking thousands of meals for evacuees and first responders, saying we were his inspiration. “If this guy is able to go to a city with no power or running water and is able to feed thousands, we’ve got to figure this out,” he said.

How to make a loaves-and-fishes miracle? You can’t possibly plan everything in advance. You show up. You spread the word. You pray. And help comes.

We needed a restaurant; we got one. We needed chefs; they came. We needed food trucks; we got them. We didn’t have gasoline, so we traded it for food. We needed more space and found it. We needed volunteers, and they came. Twenty thousand of them, making one plate at a time, feeding the many.

I’m back home now, but Patricia knows my vest is ready. Those well-traveled backpacks are ready. World Central Kitchen is working to increase resiliency in Puerto Rico so it can better withstand the next hurricane. We are working toward new solutions to combat hunger, new responses to emergency, new pragmatic approaches to disaster relief. And when the next hurricane strikes, we will be there, always working to change the world through the power of food.

For more inspiring stories, subscribe to Guideposts magazine.